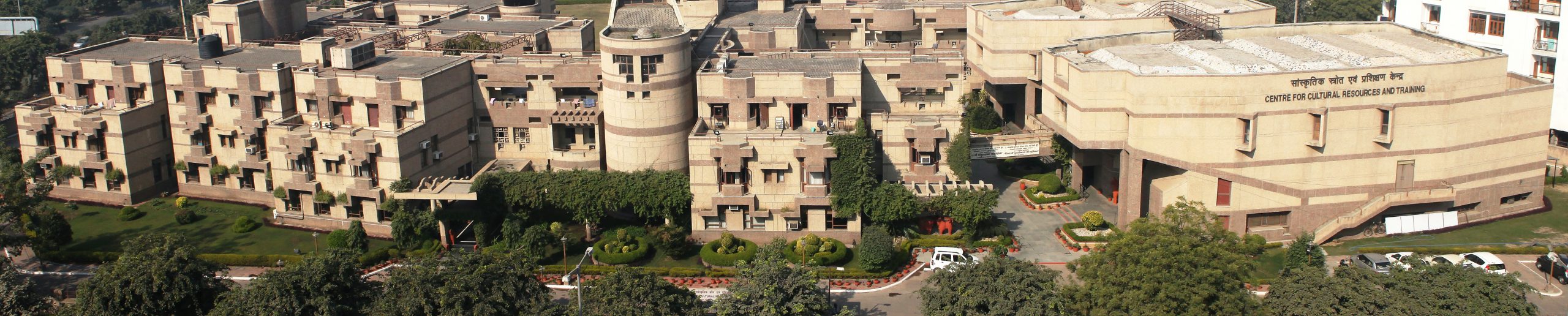

Modern Architecture

No doubt we have a great architectural heritage of temples, mosques, palaces and forts. So much so that whenever architecture is thought of in conjunction with India, images of the Taj Mahal, Fatehpur Sikri and South Indian temples are conjured up in our minds.

The question that comes to our mind is:

Do we have anything today as representative of Modern Architecture which could be compared with our old buildings? Or in even simpler terms – ‘what represents Modern Architecture in India’?

The question which is difficult to answer – demands more than skin deep analysis of modern architecture in the context of India.

The answer to this question also depends on the spirit behind it. If the curiosity behind the question concerns the quantum of construction done in post-independence years, the answer can be one impressive list of statistical figures, a fine achievement for building science and technology.

But, if on the other hand the questioning mind is concerned about new architectural and planning thought generated in the same post-independence years, which have resulted in buildings and cities suited to our socio-economic, cultural and climatical circumstances, our achievements are not very impressive so far. But considering the fact that formation of thoughts and ideas, in this relatively young field, has been going for only the last quarter of century and with the limited resources that we have, it is evident that we are on the verge of making a break-through.

It is not out of context here to go into details how things have been happening in the field of architecture in years preceeding the following independence.

Architecture traditionally, i.e., before the arrival of British on the Indian soil, was from the social point of view, a creation of spectacular sculptural forms hewn out of stone. Architectural material was stone; tools, chisel and hammer, and the aim was glorification. In contrast, the every-day needs of a common man were ruthlessly neglected. Then the British arrived on the scene, it was through them that the first introduction to elementary modern building construction and planning was introduced into India. Their aim, however, was to house their organisations, and their people and whatever was necessary to control an empire as big as India. Apart from self-serving military cantonments and civil lines, they also left the basic problems well alone. It was no intention of the British to educate Indians in the art and science of architecture. Consequently Indian minds, during the British reign, were completely out of touch with the progressive thinking taking place in the rest of the world. The most significant architectural phenomenon that took place during the first half of this century in this country was building of Imperial Delhi. This was an anachronism of the highest order, because, while at that time contemporary Europeans were engaged in most progressive thinking in architecture, Sir Edward Lutyen’s was a masterpiece in high renaissance architecture, the result of a way of thinking typical of the early nineteenth century in Europe. It is interesting to note that at the same time as the construction of Delhi, Europe was having “Heroic period of modern architecture” in such schools of thought as “Bauhaus”.

Independence woke us to a changed situation. “Time had moved on. In place of religion or royal concern with architectural immortality, this situation demanded attention to those problems that had so far been ruthlessly neglected. The ordinary man, his environment and needs became the centre of attention. Demand for low cost housing became urgent.

Industrialism that was to follow in India, spawned its own problems of townships and civic amenities for workers. Fresh migration from rural areas to existing cities also strained already, meagre housing capacities of existing cities. The very scale of the problem was and still is unnerving. 8,37,00,000 dwelling units needed throughout the country and the demand rises annually at the rate of 17,000 dwelling units, not to mention rural housing. To face staggering problems of such magnitude, twenty-five years ago, there were few Indian architects in the country and practically no planners. There was only one school of architecture in Bombay. But there was the will to build, with the limited resources and technological know-how at our disposal.

We marched ahead and built an impressive number of houses and other buildings of utilisation nature. In the process we made mistakes and learnt from them. Each fresh attempt was a step closer to building of forms more suitable for the Indian climate and socio-economic conditions. In this process, architects also became aware of the need for a certain amount of research work in new ways of building and planning if we were to face the problem squarely as they say. Since government was the agency with the largest resource, it had to carry the heaviest responsibility for construction. Need for various kinds of organisation on the national and regional level was felt. Following is the list of governmental bodies that we have today, which in some way or the other are responsible for building industry in India.

CENTRAL PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT (C.P.W.D.)

This is a national organisation with affiliated bodies at state level called Public Works Department (P.W.D.). It looks after all the construction of government office buildings, residential accommodation for government employees, institutional buildings like the I.I.T., hospitals, public auditoriums, conference halls like Vigyan Bhavan, and hotels such as “The Janpath” and “The Ranjeet”. etc. A number of other buildings, like Libraries, research institutes, airports, radio and T.V. Centres, Telecommunication building, factories and workshops are also looked after by the C.P.W.D.

Activities of the C.P.W.D. are not restricted to building construction alone. The department also looks after engineering, construction of granaries, warehouses, bridges and canals that have helped the country in its fight against food shortage.

The Horticultural wing of the department has involved itself with the creation of environmental comforts, like Parks such as Buddha Jayanti Park and Mughal Gardens.

Activities of the department at present have extended beyond the borders of the country. The Sonali-Pokhra road project in Nepal has been completed and a hospital for children in Kabul had just been completed and the department had been appointed as consultant for work of the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Institute at Mauritius.

TOWN COUNTRY PLANNING ORGANISATION

A planning organisation is responsible for physical and land-use planning on a national scale and then detailed land-use planning on regional scale. In other words this organisation is responsible for earmarking National land for various uses, such as Towns, cities, industry etc., considering factors like economy, ecology, communication etc. thereby ensuring balanced and planned physical growth of the whole nation. Apart from this the organisation is engaged in preparing development plans for existing cities such as Delhi to ensure controlled growth of these cities.

HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION :

HUDCO was set as a fInance operating body to deal with a revolving fund of 200 crores.

Its main objectives are :

(a) To finance Urban Housing.

(b) To undertake setting up of new or satellite towns.

CENTRAL BUILDING RESEARCH INSTITUTE

C.B.R.I. conducts research into various methods of economical construction and various other aspects of the building industry. It is a research oriented organisation.

NATIONAL BUILDING ORGANISATION :

N.B.O. is an organisation which acts as interface between all incoming technological information and practising architects and builders.

HINDUSTAN HOUSING FACTORY :

H.H.F. concerns itself in encouraging the technology of prefabrication throughout the country.

STATE HOUSING BOARDS TO DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITIES :

Apart from all these, are state housing boards in all the mentioned above bodies which are responsible for implementation and designing of the housing needs, and general controlled growth of the existing cities according to drawn up master-plans for development. For financial help they depend on agencies like HUDCO.

Together with the help of all the organisation, by no means an exhaustive list, government performs various roles, from public works to deployment of financial resources, from research to distribution of fundings to building industry. Much has been done, much remains to be done.

On the architectural horizon today find us with a new generation of architects and planners. Today we have nearby fifteen architectural schools throughout the country and certain equipment and knowhow of naturalized building science and technology and a growing experience with new material and methods and large scale planning. All this had not been easy.

However, it was not huge, building institutions, but individuals that have been responsible for evolving a new aesthetics bridging the hiatus between traditionalism and modernism. Painstakingly these individuals have worked, over the years, learning both from abroad and our experiences with traditional architecture, to bring about various schools of thought responsible for the spirit of modern Indian architecture. The emphasis now lies not on awesome monumentality, but factionalism with accompanying virtues of economy, simplicity and utility.

It is relevant here to go into the development of these ideas. As a matter of fact some ideas of modern architecture were not to come to us until 1950, when Le Corbusier at that time was a leading figure in architectural circles created Chandigarh, one of his most ambitious projects.

This had a tremendous impact on the mind of Indian architects, who had so far only seen-either glorious temples or forts of the past or the Imperial British capital of New Delhi in the name of modern architecture. Overwhelmed, they found this expression of modern architecture quite acceptable. It was grand and sensational and at the same time was based on rational basis of climatic analysis and planning freedom. In the years to follow, buildings spring up all over India which had similar expression and the same materials. But ideas of Le Corbusier had to be crystallized before they could be adopted in India. Some realized that concrete and plastic forms were after all not the solution for all Indian architectural problems, howsoever sensational they might be.

There was another parallel phenomenon going on at the same time which was to influence the course of modern architecture in India to come. Indian architects were going to Europe and America to seek higher education and cultural inspiration. The Indian architectural community took its inspiration from ideas developed in the western world. During the sixties these architects who received their education in the western countries commanded high positions as professionals as well as teachers. They taught, practiced and experimented with what they had learnt in the west against the harsh realities of India. The process of fermentation of ideas was turned on. There were many realizations that were to form the rational basis for architecture to come.

First of these realizations was that if we have to do anything worthwhile in India for Indians under Indian socio-economic and climatic conditions, the west was no place to look for inspirations or solutions. We will have to evolve our own patterns of development and physical growth, our own methods and materials of construction and our own expression of foregoing. This realisation created a sense of vaccum and because of the poignancy of the feeling of vaccum, the search began, and architects started looking in different directions for various answers. In each direction partial perception of truth was declared as the total truth. The fact however, remains that in each direction we have moved closer to rational basis of modern architecture. One of the first places where Indian architects looked for inspiration for expression of total architecture of India, is our own village and folk architecture. Architects studied with keen interest the way people solved problems long before western influence was felt in India. From desert settlements of Jaisalmer, to village developments of hills, plains and sea-coasts, all became the focus of study. Complex planning were analysed and looked into for inspirations. There are some daring architects who have gone as far as to study the human settlements in the heavily populated areas of existing metropolitan cities, built without the help of architects, looking for solutions of high density, low rise economical housing; a challenging problem for India. It is the contention of these farsighted architects, with a hard nosed realism, that in such kinds of dense developments, with simple methods of construction and conventional low cost materials, when laid out in a planned manner, that we will find the answer urban housing for our really poor masses. While some of these architects were busy looking for answers in what we already have in our traditional settlements, others were exploring how industry can be made use of in solving the aspect of building problems. Prefabrication has potential in large scale housing, large span structures and industrial buildings on anywhere were repetitive units can be employed. But so far in India, industrialization of the building industry has not made great headway for lack of technological infrastructures to support it, therefore its influence is only limited to fascination of imagery. However, one aspect of technology that can be successfully applied in architecture is invention and manufacture of new building materials from industrial waste to replace the traditional building materials like steel and cement of which there are tremendous shortages.

There is the growing realization among architects that just to build visually beautiful buildings will be useless, unless it is backed by infrastructure of services, such as water supply, electrical supply and communication system of rapid mass transit, etc. In other words it is not an individual building but the total environment that matters. All this calls for serious attention on patterns of physical growth that will take care of layouts of all these services in an organised manner.